Introduction: Why We Need to Rethink Economics

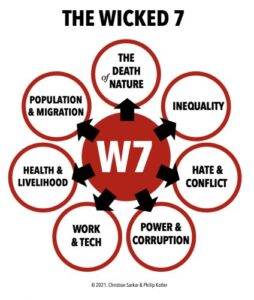

The 21st century challenges the foundations of mainstream economics. Climate breakdown, rising inequality, and ecological overshoot demand a new approach.

Doughnut Economics, developed by Kate Raworth, proposes a shift: from a growth-focused economy to one that meets human needs within planetary boundaries.

What Is Doughnut Economics?

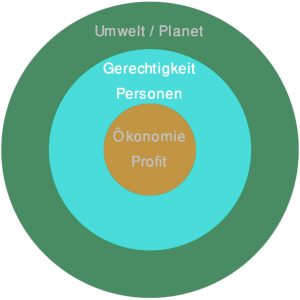

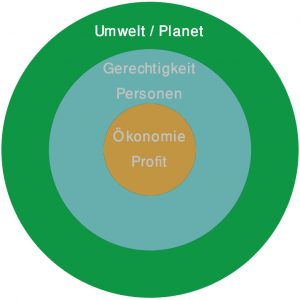

Doughnut Economics visualizes a safe and just space for humanity: a “doughnut-shaped” area where people’s essential needs are met without breaching ecological thresholds.

The inner ring represents the social foundation – the minimum standards for a decent life. The outer ring marks the planetary boundaries – the ecological ceiling we must not exceed.

Between these two rings lies the doughnut: the sweet spot where humanity can thrive.

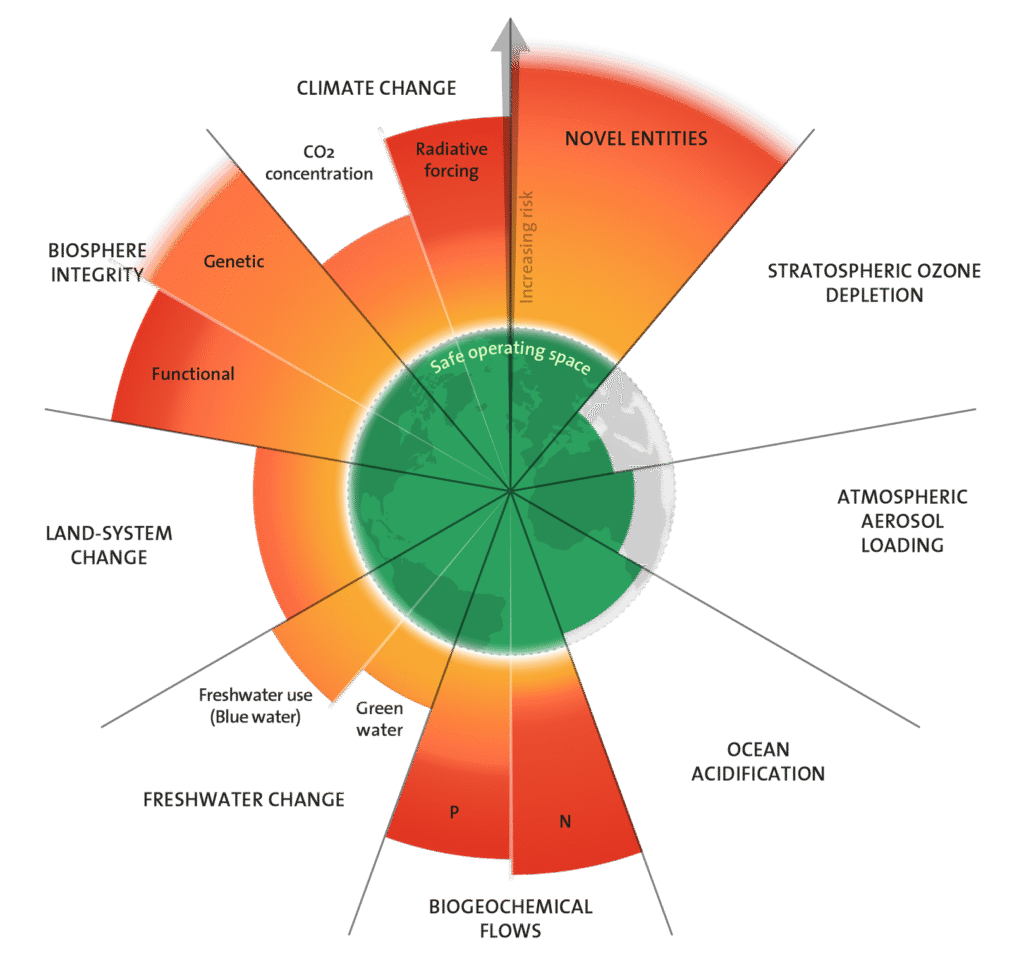

The Planetary Boundaries

Originally conceptualized by Rockström et al. and later updated by the Stockholm Resilience Centre (2023), the planetary boundaries framework now assesses nine Earth system processes. As of the latest research, six of these nine boundaries are already breached.

🌍 The Nine Boundaries:

- Climate Change – Atmospheric CO₂ & surface temperature remains well above safe levels

- Biosphere Integrity – Accelerated species extinction and ecosystem degradation

- Novel Entities (e.g., plastics, chemicals) – Unchecked chemical pollution

- Stratospheric Ozone Depletion – The ozonhole that protects us from UV-radiation

- Ocean Acidification – causing marine ecosystem to tip

- Freshwater Change – Disruption of the blue water (hydrological cycle) and green water (bound in plants and soil)

- Land-System Change – Loss of forests and soil functions

- Nitrogen & Phosphorus Flows – Overuse in agriculture leading to

- Atmospheric Aerosol Loading – changing moonsoon and rainfalls next to being harmful to humans

🔗 View full 2023 update – Stockholm Resilience Centre

These boundaries are interconnected, and their transgression increases the risk of triggering tipping points in Earth’s systems.

Host a Planetary Boundaries Workshop

I offer interactive workshops using the Planetary Boundary Fresk – a science-based and creative way to explore Earth’s ecological limits and what they mean for us.

📩 Want to organize a workshop for your team, university, or community?

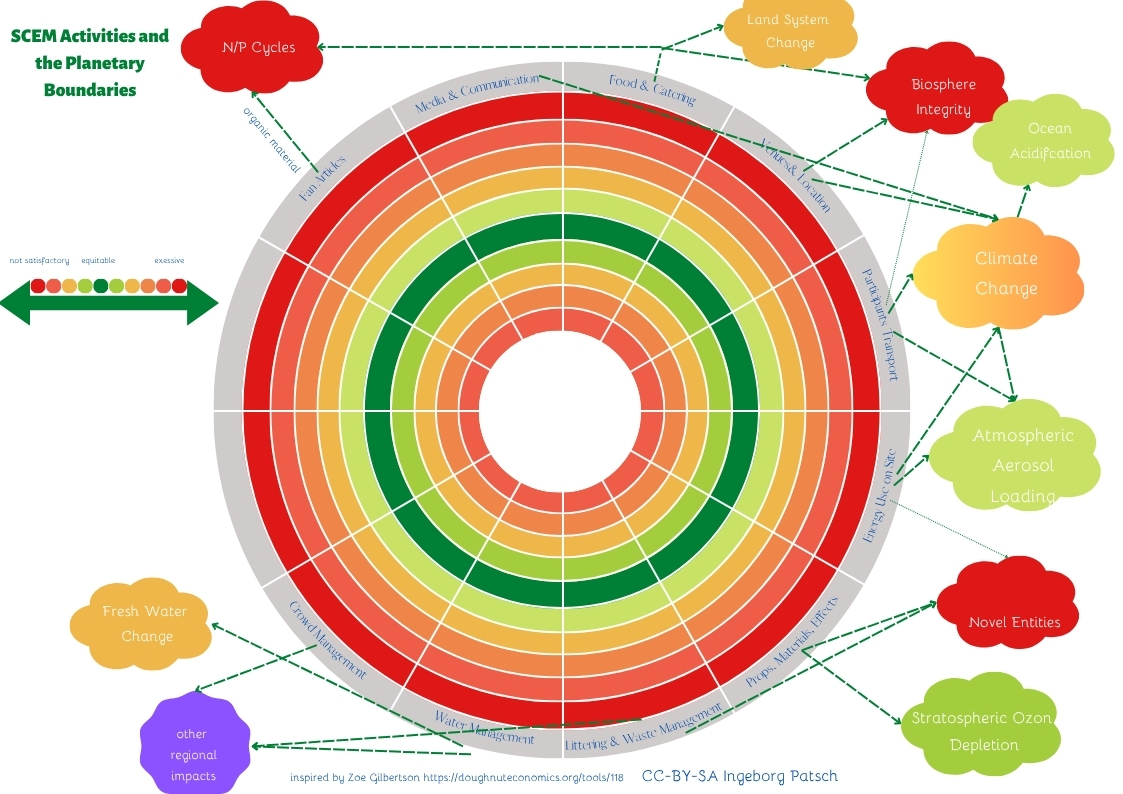

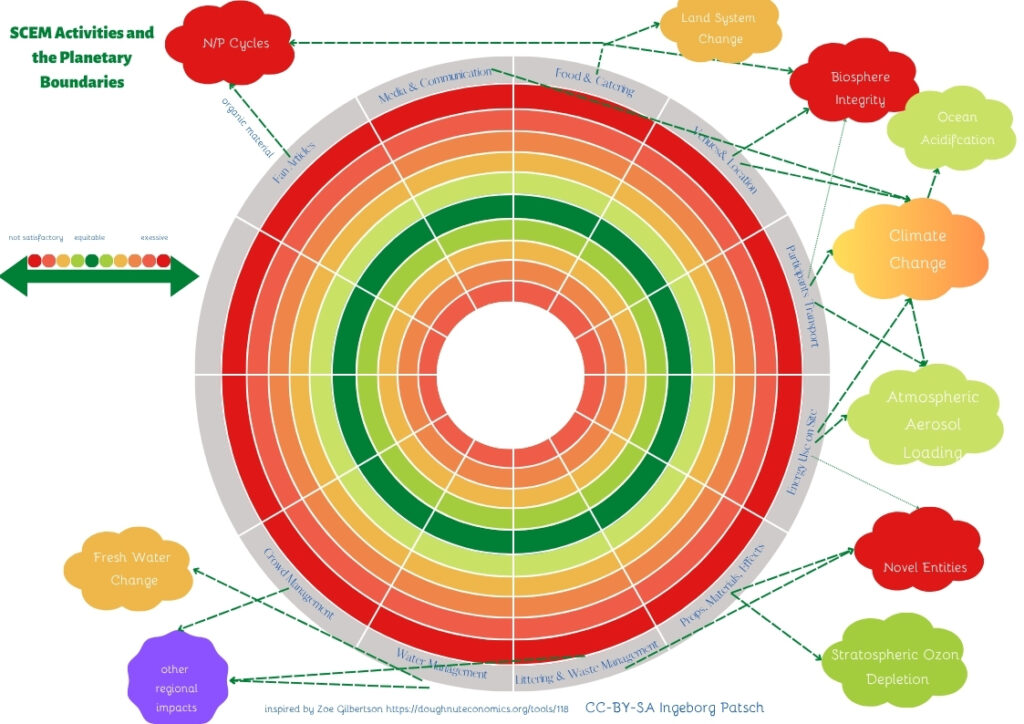

Integrating Doughnut Thinking into Sport, Culture, and Event Management

As part of my university teaching, I developed a custom adaptation of the Doughnut Economics model for the fields of sport, culture, and event management. The adapted doughnut links common sectoral activities (e.g., food & catering, media & communication, transportation, water management) with social outcomes and ecological constraints.

📄 👉 Download the interactive worksheet now to explore how your event or initiative aligns with the doughnut principles.

This visual helps students and practitioners rethink the impact of their work within a regenerative and distributive economic lens.

Why Doughnut Economics Resonates Today

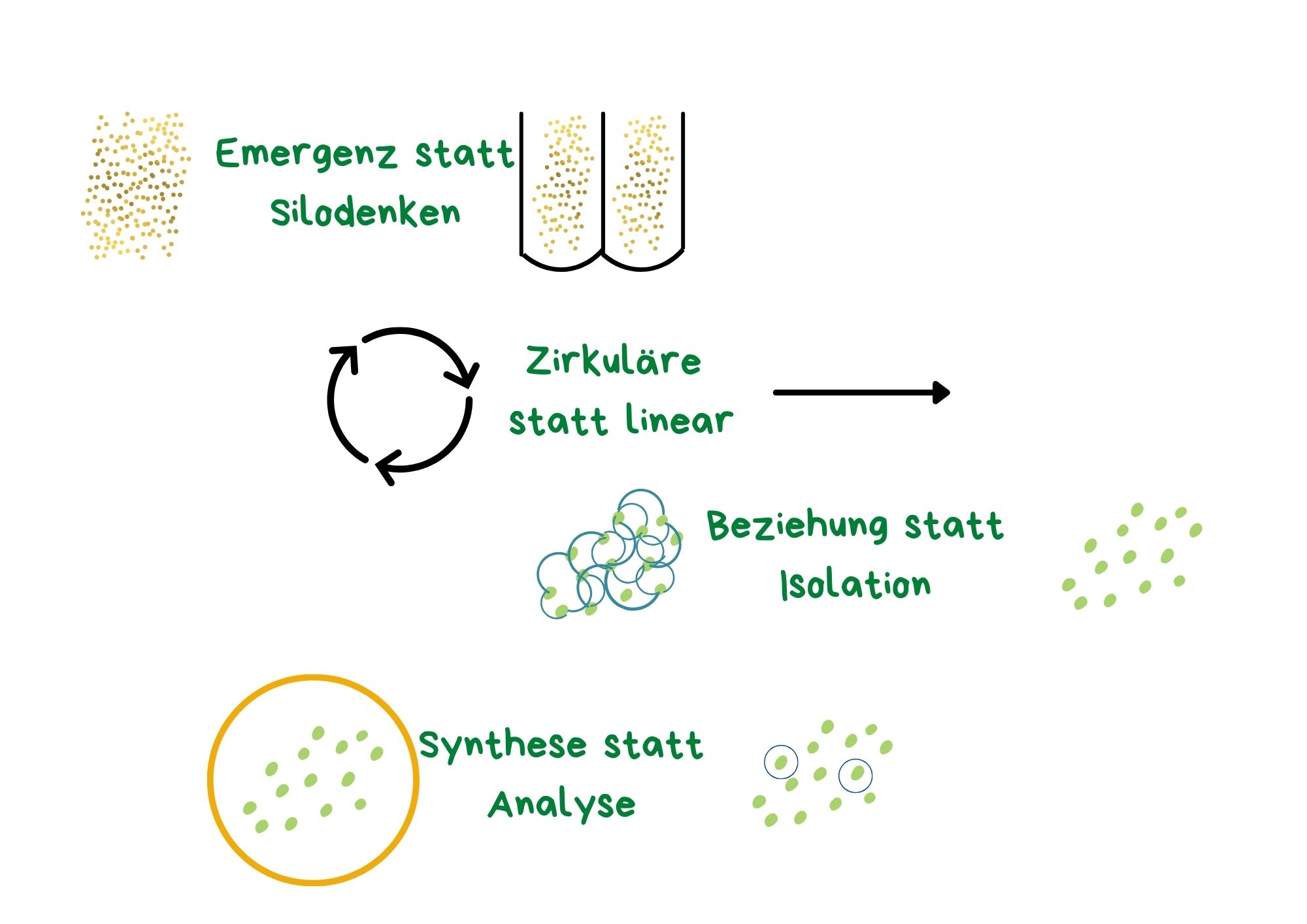

Doughnut Economics breaks away from the outdated paradigm of GDP growth as a proxy for progress. It asks deeper questions:

- How much is enough?

- Whose needs are being met?

- At what ecological cost?

It offers an integrated view of sustainability, equity, and systems thinking, accessible for policy, education, and local action.

Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities & Threats of Doughnut Economics

Doughnut Economics presents a bold and accessible alternative to mainstream economic thinking. Like any framework, it comes with strengths, limitations, and implementation challenges. Together with one of my students, Elena Dax, we developed the following SWOT analysis to critically assess the concept and its practical potential:

✅ Strengths

- Balanced system design – Integrates both the needs of people and the ecological limits of the planet.

- Holistic perspective – Highlights the joint relationship between environment, society, and economy (the three E’s of sustainability: environmental, economic, ethical).

- Accessible visualization – The circular doughnut model is simple and engaging, making it easier for non-experts to understand complex systems thinking.

- Educational & inclusive – Encourages broader participation in economic discourse, particularly from younger generations and those unfamiliar with traditional economic theory.

❌ Weaknesses

- Potential oversimplification – The visual model can be seen as too basic to capture economic complexities.

- Lack of practical tools – Some authors criticize that it offers no concrete policy roadmap or prioritized action steps for implementation.

- Western-centric perspective – Critics (e.g., Gudynas, 2012) argue that the model reflects predominantly Western thinking, which may limit its applicability in diverse global contexts.

- Limited individual guidance – There’s little orientation on how individuals or small groups can take action.

🌱 Opportunities

- Global adaptability – The model can be localized to fit diverse cultures, cities, governments, and communities.

- Multi-level application – Suitable for use in business, urban development, education, and policy.

- Encourages innovation – Inspires new ways of thinking about economics, particularly among students and changemakers.

- Open framework – Its flexibility allows for new data, feedback, and evolving priorities to be incorporated over time.

⚠️ Threats

- Lack of clear change processes – The steps to transition from theory to practice are vague, which can hinder implementation.

- Resistance to change – Many individuals and institutions are unwilling to give up current privileges or shift priorities.

- Risk of being dismissed – Policymakers and economists might reject it as too simplistic or radical, slowing broader adoption.

- Social tension – Systemic changes proposed by the model may create friction between different socioeconomic groups.

Making It Actionable: From Theory to Practice

Many cities (e.g., Amsterdam, Brussels) and organizations are already experimenting with the Doughnut model for real-world decision-making.

It is being applied to:

- Urban planning

- Corporate sustainability

- Educational curricula

- Civil society initiatives

The model remains open-ended – and that’s a strength. It invites collaboration, co-creation, and contextual adaptation.

Checkout local organizations and networks that implement Doughnut Economics in their cities.

Conclusion: Economics for the 21st Century

Doughnut Economics gives us the language and the lens to ask:

What does a thriving economy look like when we respect ecological boundaries and social justice?

It doesn’t promise easy answers – but it offers the space to ask better questions.

References

Gudynas, E. (2012). Is doughnut economics too Western? Critique from a Latin American environmentalist. Views & Voices, Analyses and debate on international development issues. Blog, Oxfam. https://views-voices.oxfam.org.uk/2012/02/is-doughnut-economics-too-western

Raworth, K. (2017). Doughnut Economics. Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist. London: Penguin Random House.

Raworth, K. (2018). Kate Raworth. Exploring doughnut economics. Personal website. https://www.kateraworth.com/doughnut/

Sen, A. (1999). Development as Freedom. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Steffen, W., Richardson, K., Rockström, J., Cornell, S.E., Fetzer, I., Bennett, E.M., Biggs, R., Carpenter, S.R., de Vries, W., de Wit, C.A., Folke, C., Gerten, D., Heinke, J., Mace, G.M., Persson, L.M., Ramanathan, V., Reyers, B. and Sörlin S. (2015). Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet. In: Science 347(6223), 1259855. https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/bitstream/1885/13126/3/1259855.full.pdf

United Nations – UN (2015). Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015. Document A/RES/70/1. New York.

Host a Planetary Boundaries Fresk

I offer engaging workshops using the Planetary Boundaries Fresk, a science-based tool to explore Earth system limits and their relevance to our work and lives.

📩 Interested in organizing a workshop for your university, team, or community?